Unearthing the Ancient: The Discovery of Eridu, One of the Oldest Cities on Earth

In the heart of the arid Iraqi desert, beneath layers of earth and time, treasures of history lay hidden, waiting to be uncovered. Among these treasures is Eridu, an ancient city that bears witness to the dawn of civilization. The journey of discovery began with the unassuming mounds scattered across the flat terrain, seemingly devoid of promise. Yet, as archaeologists began to probe deeper, they unveiled a narrative that reshaped our understanding of Sumerian culture and its enduring legacy.

The Initial Dig: How It All Began

In 1854, a seemingly routine expedition led British official John George Taylor to the dusty hills of southern Iraq. Tasked by the consul general in Baghdad, Taylor was to investigate Tell Abu Shahrain, a site comprised of various tells—mounds formed from the detritus of ancient civilizations. However, his first excursion yielded disappointing results. In his report published the following year, Taylor lamented, “My visit this year to Abu Shahrein has been unproductive of any very important results.” Disheartened by the absence of magnificent statues, grand inscriptions, or royal palaces, he viewed his findings as rather mundane.

Nevertheless, among the rubble and stonework, Taylor stumbled upon remnants that would eventually pave the way for profound discoveries. He cataloged walls, complex drainage systems, and the remnants of decorated limestone columns. Most notably, he recorded finding a black granite lion—a discovery that, at the time, felt inadequate for justifying further investigation. Little did he know, beneath the surface lingered the ruins of Eridu, one of the oldest cities known to humankind.

Taylor's Passion and the Allure of Antiquity

John George Taylor was no stranger to the history of the Near East. His travels from 1851 to 1861 allowed him to explore significant archaeological sites, including Tell el Muqayyar, known as Ur—another iconic hub of Sumerian civilization. Despite his lackluster findings at Tell Abu Shahrain, the fragmented relics of Eridu ignited a spark of curiosity that would loom over the centuries.

Eridu, founded approximately 5,000 years ago, played a pivotal role in Sumerian culture, which is recognized as the world's earliest known civilization. It flourished between the fourth and second millennia B.C. in the region now identified as Iraq. Historical narratives highlight Eridu’s significance as one of the first royal cities, as chronicled in the Sumerian King List—a document inscribed in cuneiform that emerged toward the close of the third millennium B.C. The list mentioned five cities before an event dubbed “the Flood,” with Eridu honored as the first: “After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu...”

Additionally, Eridu was revered as the sacred abode of Enki, the god of water and wisdom. Since time immemorial, pilgrims journeyed to this ancient city to pay homage at its magnificent temple, which stood testimony to the spiritual and cultural richness of the Sumerians.

Renewed Interest in Eridu

Though Taylor’s findings seemed to dwindle in importance, they did not vanish into obscurity. Scholars and archaeologists remained intrigued by what lay forgotten in the sands of time. In the aftermath of World War I, officials at the British Museum sought to reignite the flame of curiosity. In 1918, Assyriologist Reginald Campbell Thompson was enlisted to spearhead excavation efforts, using Ottoman prisoners of war to assist in surveys of the area.

The real breakthrough at Eridu, however, did not occur until 1946. With Iraq having gained its independence from Britain in 1932, there was renewed impetus for archaeological pursuits that would contribute to the cultural narrative of the newly-formed state. The Department of Antiquities of Iraq commissioned Iraqi archaeologist Fuad Safar, alongside British archaeologist Seton Lloyd, to return to the mounds of Eridu. Safar and Lloyd approached the dig with a mix of hope and anticipation, aware that the site held the potential to unlock vital chapters of Mesopotamian history.

Beneath the Surface: Discovering Layers of Civilization

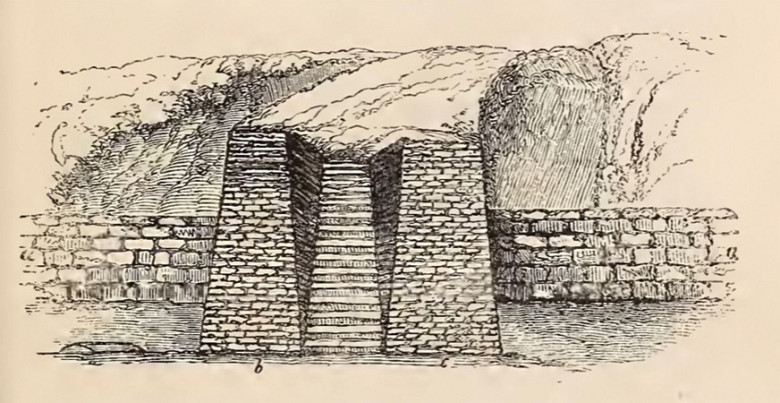

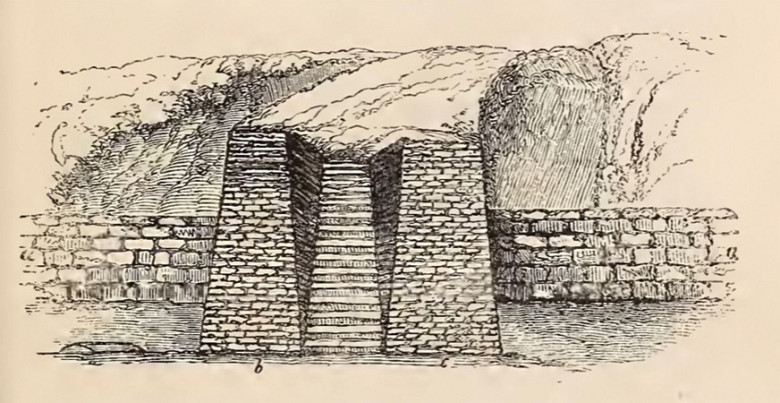

The two archaeologists focused their efforts on Mound 1, standing impressively at 82 feet high and spanning an area of approximately 1,900 by 1,770 feet. As they began to excavate, they quickly uncovered the foundations of an unfinished ziggurat that dated back to the late third millennium B.C. This monumental structure was commissioned by a ruler of the 3rd dynasty of Ur. However, what truly captivated their attention was what lay beneath those ruins.

With each layer they peeled away, a timeline of urban history unfolded. They traced the initial construction back to the Uruk period (4500–3200 B.C.) and discovered remnants from the earlier Ubaid period (5300–3800 B.C.). Through their diligent excavation, they unearthed multiple reconstructions of the temple of Enki, revealing the city’s long-lasting worship traditions and the evolution of its architectural marvels.

In the words of Italian historian Mario Liverani, the temples of Eridu were "reconstructed and expanded after each collapse.” These successive temples not only reflected the faith of the community but also chronicled the city’s shifting social structures and increasing complexity.

The Architectural Journey of Eridu’s Temples

The temple of Enki served as a focal point for worship over the centuries. Each iteration of the structure grew larger, more elaborate, and grander than the last—signifying a transition from familial worship in domestic spaces to ritualistic gatherings in monumental architecture. These changes marked the emergence of complex social hierarchies within Eridu, as the community grew from small bands of individuals to organized city-states.

By approximately 3200 B.C., the frequency of temple reconstructions began to wane. With the zenith of Sumerian power under the Ur III dynasty occurring a millennium later, a grand ziggurat was eventually erected atop the ruins of its predecessors, solidifying Eridu’s status in history.

Surveying Mound 1, it became evident that it was a veritable stratigraphic record, revealing 18 distinct layers of human habitation. Archaeologists meticulously documented the remains of six successive temples, each iteration telling a different story of Eridu’s ascendancy to prominence in the landscape of ancient Sumer.

The Evolution of a City

Even as Eridu’s role as a political and religious powerhouse began to wane, it retained significance as a site of pilgrimage. Surrounding tells offered further insights into the timeline of this ancient metropolis. Mound 2, for example, revealed remains of a palace complex dating back to the early third millennium B.C. In contrast, Mounds 3, 4, and 5, showcasing pottery from the second and first centuries B.C., outlined a landscape that, while sparsely populated, still retained echoes of its storied past.

Despite the interruptions caused by political turmoil and the challenges of archaeological work in the region, the discoveries at Eridu beckoned to researchers from around the globe. Safar and Lloyd’s extensive findings were finally published in 1981, serving as a cornerstone for future studies. Today, even amid ongoing instability in Iraq, teams of Italian and French archaeologists are eager to return, driven by a passion to unearth even more layers of history from the remnants of Eridu.

Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of Eridu

Eridu is not merely a city buried in the sands of time; it is a cornerstone of human history, providing critical insights into the very foundations of civilization. The archaeological journey—beginning with John George Taylor's unassuming expedition and culminating in the expansive digs led by Fuad Safar and Seton Lloyd—demonstrates the undying human quest for knowledge and connection with our past.

As modern archaeologists continue their work, they strive not only to uncover more lost relics but also to weave the rich tapestry of Eridu’s history into the broader narrative of humanity's journey. Each artifact, each stone, and each narrative clawed back from the earth serves to remind us that the threads of our shared existence are ancient, intricate, and profoundly interconnected. The story of Eridu challenges us to reflect on the very essence of civilization, the relentless drive of the human spirit, and the timeless quest for understanding our place in the world.

Comments

0 comment